Reinvigorating Land through Conservation

How One San Luis Valley Family’s Easement is Revitalizing its Ranch

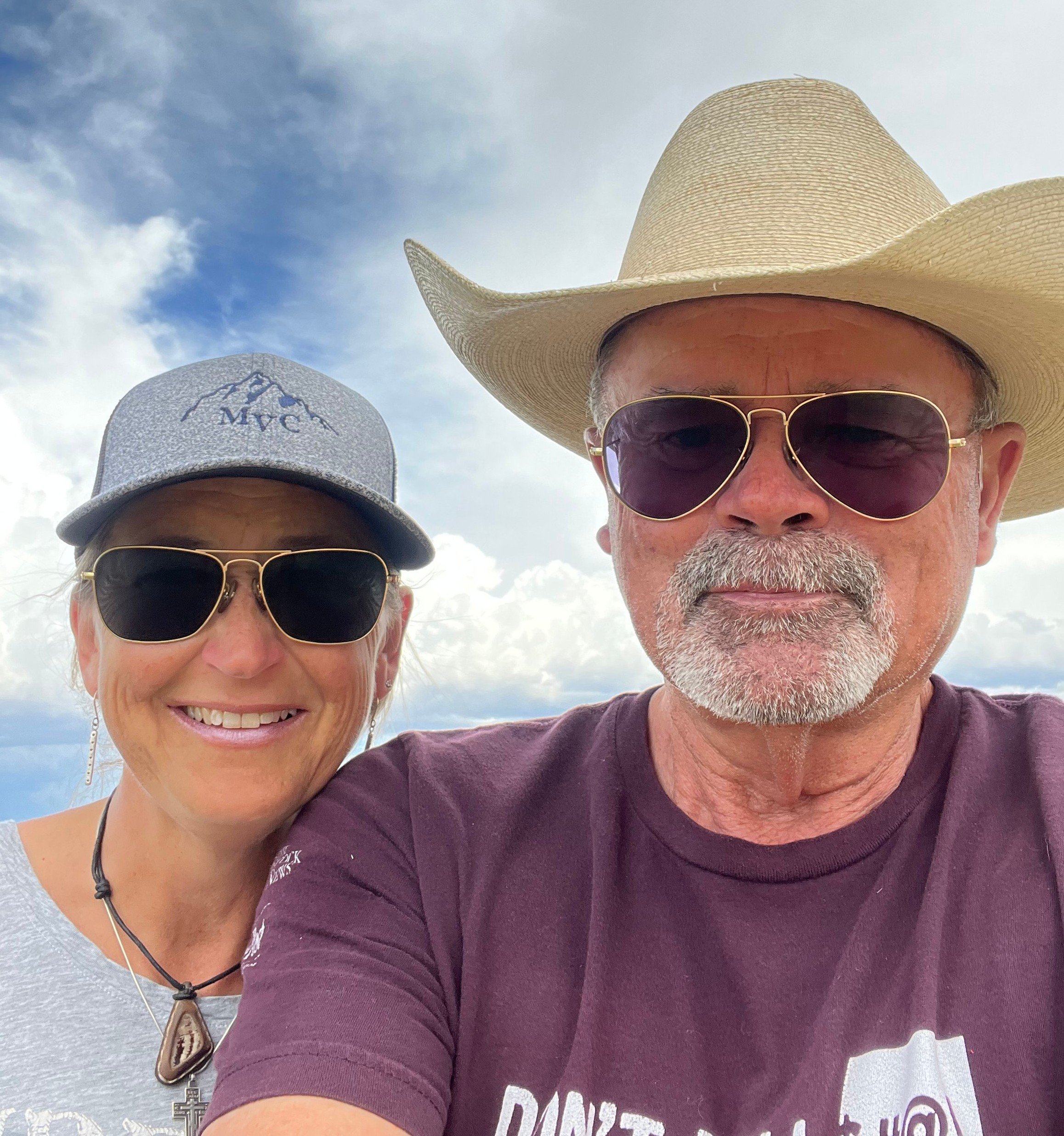

Landowners: Peter and Leah Clark

Partner land trust: Rio Grande Headwaters Land Trust

Location: San Luis Valley

Topics: Water management, experimentation with crops and irrigation

Peter and Leah Clark have owned land in Colorado’s San Luis Valley since 2001. The couple has spent the better part of their two decades there, fostering a symbiotic relationship with the land and with their neighbors – one of which happens to be the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

The couple both are alumni of the U.S. Forest Service and moved to the Valley in 2000 when Peter was reassigned as forest supervisor of the Rio Grande National Forest. They knew this would be their last move before Peter’s retirement, and were looking for property with agricultural potential where they could spend the next chapter of their lives. They had looked at several properties when a local realtor showed them 220 acres that abutted the Monte Vista National Wildlife Refuge.

Immediate appeal

Peter and Leah were immediately interested because of the land’s farming and ranching potential, its wildlife resources, its scenic views and the unlikely possibility that adjacent lands would ever be developed.

During negotiations, the owner at the time decided to include the property in a broader deal between the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Colorado Division of Wildlife and Trust for Public Land (TPL). The Clarks were able to negotiate a deal and purchased the property from TPL in 2001. Two months later, they donated a conservation easement on the property to the Rio Grande Headwaters Land Trust (RiGHT), a brand-new land trust. It was RiGHT’s first conservation easement.

The Clarks’ property includes a center-pivot irrigation circle, which is operated using a high-capacity, deep irrigation well. The well is artesian and geothermal, and has contributed to valuable wetland habitat and provided a winter water source for livestock. The property also contains historic meanders of the Rock Creek/Spring Creek drainage complex. The government has identified Rock Creek as a stream worthy of improving and protecting, as the area has historically been home to abundant waterfowl and a variety of wetland and riparian species, both plants and animals. However, increasing droughts and stringent – but necessary – water regulations have threatened these environments.

The Clarks have worked hard to improve the quality of the agricultural land, restore the area for wildlife and, ultimately, protect the property from development for the long term.

“When we started, there was a worn-out circle of alfalfa,

60 acres of wet meadow and nothing else.”

Not an easy road

When the Clarks bought the property, the soil was not in the best shape, but there was a deep artesian well on site. There were no livestock handling facilities, and fences were either non-existent or falling down. There was not a single structure – not even a house or a hay barn. “When we started, there was a worn-out circle of alfalfa, 60 acres of wet meadow and nothing else,” Peter says.

Over the years, the Clarks have participated in numerous resource management initiatives with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife service, Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s Habitat Partnership Program, several National Resources Conservation Service programs and, most recently, Colorado Department of Agriculture’s STAR Plus program, which focuses on soil health.

To address their primary concerns and manage their water and soil resources, the Clarks have undertaken a variety of projects. They have replaced their ditch irrigation with gated pipe irrigation, and employed different nozzle packages on their center-pivot irrigation to manage the water more efficiently. They’ve experimented with their farming operation by incorporating new crops and rotating crops; growing cover crops; winter grazing those cover crops; and undertaking other farming methods that harken back to practices more common before farming became so highly mechanized.

Their agreement is flexible and empowers the Clarks to make their own decisions about what to do with the land.

Currently, the Clarks are working to convert half of their center-pivot irrigation into permanent mixed grass that they can use for grazing as well as for harvesting and selling hay. None of that work has been easy.

What has been easy is working under the terms of the conservation easement, which is held by RiGHT. Their agreement is flexible and empowers the Clarks to make their own decisions about what to do with the land. In 20 years, the Clarks have been able to make extensive improvements to their property, turning it into a vibrant ranch that includes a herd of registered SimAngus cattle, horses to help manage those cattle and an ongoing farming operation.

A lasting impact

The upside of having an easement has been multifold. It enables the Clarks to build a legacy for their son, and it ensures that this beautiful real estate won’t ever be subdivided or developed. This was important to Peter, who grew up seeing his family’s ranch in California “chopped up and sold in pieces.” That experience shaped how he would like to treat the land: “I always wanted to reestablish something. Legacy is about continuity and management of lands to pass on,” he says.

Conservation of the property has provided the Clarks with long-term protection of unobstructed, striking views of the area and has protected and revitalized the wildlife attributes of the property.

“The conventional wisdom used to be that placing a conservation easement on a property devalued it by some amount. I believe in many instances, that is no longer the case. Depending on a person's perspective, I think there are folks out there who see conservation easements as a value-added feature, especially if their neighbors have one too. Easements can also help farmers and ranchers stay in business or even help newbies get into the business in a very competitive market,” says Peter. The Clarks have used any money generated on the property to reinvest in their business, including purchasing equipment, livestock and other items needed for the operation.

Ultimately, the terms of the Clarks’ conservation easement closely align with the way they manage the land. “As long as I maintain the conservation values, it’s not difficult to keep doing what needs to be done. And you just need to know what you’re agreeing to when you sign up for it,” he says.

On the other hand, he adds, “If you have designs on subdividing your property, then a conservation easement probably isn't for you. Fragmentation is the most detrimental thing you can do to the landscape.”

The Clarks want to ensure the land stays the way it is – natural and undeveloped. And while they hope to pass the land on to their son, they also hope more private landowners will consider the benefits of private lands conservation, so we all have something to pass down to Colorado’s future.

“I always wanted to reestablish something.

Legacy is about continuity and management of lands to pass on.”

Produced in partnership: